“It’s the best time to write when you’re fresh, you know,” Chigozie Obioma, 28, said.

The first sign of light inspires him, he said. Until it hits, he tends to pull himself away from the page to track the moon’s downward path.

“I can almost calculate when it will completely obliterate itself,” he said.

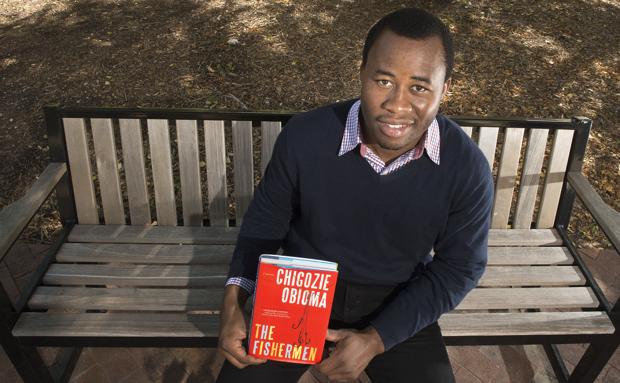

This is not to say Obioma, a first-year creative writing assistant professor at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, adheres to an early morning regimen. He writes when his schedule allows it. It’s just that these days, with the Booker award ceremony looming on Oct. 13, his days often include multiple interviews about his first novel, “The Fishermen.”

When the Man Booker Prize announced its longlist in late July, Obioma said in an interview on the Booker website that his well-received first novel, released in February in the UK, had already grown “comatose” prior to the nomination announcement. Though it earned glowing praise, the review cycle lasted a few weeks, or a month at best, he said. And then the buzz subsided. A similar cycle began in the U.S. after its release here in April.

"It basically had run its course," Obioma said during a conversation at his office in Andrews Hall. "What the Booker Prize has done is pump new life into the book.

"The Booker has that power, that resurrection power."

While the prominent award might breathe life back into a novel, it leaves only its author to speak for it. This has been something of a challenge for an author whose book jacket photo is just a cellphone pic a friend snapped midsentence during a lunch conversation.

"It's actually very difficult to plumb into the depths of the book,” Obioma said. “With every interview, I feel like I didn't say even half of what I think the book is trying to do. And the more I feel like I speak about it, the more I feel that I am spoiling it for the reader. Because it's an intensely complex book."

But in conversation, Obioma discusses the themes, the characters, the Grecian elements, the post-colonial struggle of his Nigerian homeland and more. He highlights philosophical principles key to the book's structure, like the Igbo theory, "Egbe belu, Hugo e belu -- where one thing lives, another lies beside it."

"I think in terms of storytelling, it means that nothing can exist on its own without being compared to something else," said the author whose first work has been compared in reviews to that of "Things Fall Apart" by author Chinua Achebe.

“The Fishermen” takes place in Obioma’s hometown, Akure, in the Ondo State of Nigeria. The story of a family grappling with the ramifications of a madman’s prophecy unfolds during a seminal decade in the nation’s history.

“It starts off from 1993,” Obioma said. “After years and years and years of military rule. Nigeria made an attempt, a botched attempt, at civilian democracy. But the election was annulled. And M.K.O. Abiola's presidential win was aborted. In 1999, Nigeria was able to, after years of international pressure, go back to democracy. And the first time that democracy was not interrupted, that it was actually a four-year period, was 2003.”

The author grew up in a similarly large family as the one portrayed in “The Fishermen.” (He began the book during his first time away from them, some 4,000 miles away at college in Cyprus. It is dedicated to Obioma’s 11 brothers and sisters, whom their father lovingly called his “battalion.”) But Obioma said only two characters in the book qualify to him as autobiographical -- the river where four brothers sneak off to fish and “about 60 percent” of the father, Eme, whose stern orders to better themselves are betrayed by going fishing.

The narrator, Benjamin, who speaks both as a 9-year-old and a transformed adult during the novel’s uniquely structured course, happens to share along with Obioma a childhood fascination with Homer’s works and a vivid memory of watching Nigeria take gold in the '96 Olympics soccer competition. Eme also tells Benjamin he will become a professor, and lashes out anytime any of his sons stray from the paths he's set for them.

"My dad was the one who really encouraged me, as a little boy,” Obioma said. “He started by telling me stories. When you say you want to be a writer in Nigeria, as I used to do as a child, so many people were afraid for me. They were like: 'What are you going to do? How are you going to make money?’ Because we don't have a very strong reading or even publishing industry in Nigeria. So they were always trying to dissuade me and try to push me into something else. But the man was really like, 'Let him be.'”

Obioma's father will join him in London when he travels there next week for the Man Booker Prize reception. So will his publisher, editor, agent, publicist and uncle, but Obioma said the one-of-a-kind, leather-bound copy of "The Fishermen" he'll receive whether he wins or not likely will go home with his father.

Eventually, Obioma said, he wants to return home to Nigeria, too. When he arrived at UNL this fall, after earning his M.F.A. at the University of Michigan, he said in a university release that he was drawn here in part because English professor and Prairie Schooner editor Kwame Dawes was doing "amazing things" for African literature, through the Schooner and the African Poetry Book Fund.

"I want to see, once I am settled here, if I can take that to a higher level and try to start off a kind of program or initiative that would stimulate a reading culture (in Nigeria)," Obioma said. "I think one of the ways to stamp out corruption, which is one of the biggest problems we have across Africa, especially in Nigeria -- I think we can deal with it in a way through reading.

"The people who are corrupt are not uneducated. They are (educated). So I can't say education is the problem at all. But I think we can maybe through a pure empathy, through literature, if people empathize with the poor, they will not feel the need to steal the money, to embezzle government funds. So I think literature can be a way to engender empathy in people. So I want to do something through that."

Obioma said he also wants to finish his second novel here, the one he's working on in his sunrooom. He has a title for it, "The Falconer," which happens to be the title of a chapter in "The Fishermen."

"I'll be telling the story of a man by comparison to what are the functions of a falconer, someone who takes care of birds, who is in charge of them," he said. "I look forward to sharing the novel with the world."

Reach the writer at 402-473-7438 or cmatteson@journalstar.com. On Twitter @LJSMatteson.

No comments:

Post a Comment